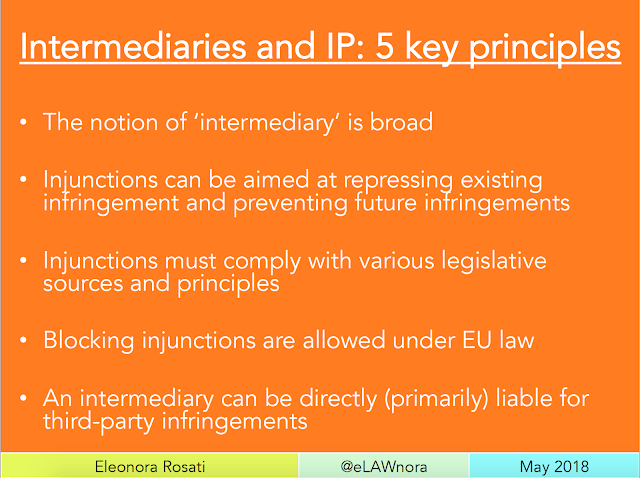

Intermediaries and IP: 5 key principles of EU law

|

| Marcus felt slightly challenged after reading all those CJEU IP decisions ... |

It is a truth universally acknowledged, that online IP enforcement must be (increasingly) in want of an effective involvement of intermediaries in the enforcement process.

The topic thus turns to intermediary injunctions, ie something that at the EU level is substantially enshrined in two pieces of legislation, these being: the InfoSoc Directive (Art 8(3)), as far as injunctions in copyright cases are concerned; and the Enforcement Directive (Art 11, third sentence), with regard to the other IP rights.

The relevant provisions have similar content.

Art 8(3) states that "Member States shall ensure that rightholders are in a position to apply for an injunction against intermediaries whose services are used by a third party to infringe a copyright or related right."

The third sentence of Art 11 provides that "Member States shall also ensure that rightholders are in a position to apply for an injunction against intermediaries whose services are used by a third party to infringe an intellectual property right, without prejudice to Article 8(3) of Directive 2001/29/EC [that is the InfoSoc Directive]."

Intermediary injunctions are available irrespective of whether the intermediary targeted by it has any liability for the infringement committed by users of its services and is therefore distinct from both issues of safe harbours protection as per the E-commerce Directive and issues of primary (direct) liability or the intermediary itself.

Having said this, it seems fair to say that the actual EU framework for intermediary injunctions and, more generally, intermediary liability has been shaped through the wealth of cases that have reached the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) over the past few years by means of references for a preliminary ruling.

But what core principles can be extracted from the resulting CJEU decisions?

Principle #1 - In its case law - including the recent judgments in Tommy Hilfiger [here] and Mc Fadden [Katposts here] - the CJEU has clarified that the notion of 'intermediary' is both loose and broad: for an economic operator to be considered as ‘intermediary’ it is sufficient that they provide – even among other things – a service capable of being used by one or more other persons in order to infringe one or more IP rights.

Principle #2 - This is a principle that the CJEU provided in its landmark decision in L'Orèal when it held that the injunctions referred to in the third sentence of Article 11 differ from those referred to in the first sentence of that provision: while the latter are addressed to infringers and intend to prohibit the continuation of an infringement, the former are addressed to the “more complex” situation of intermediaries whose services are used by third parties to infringe one's own IP rights. Also taking into account the overall objective of the Enforcement Directive, ie to ensure an effective protection of IP rights, alongside the provision in Article 18 of the E-commerce Directive and Recital 24 in the preamble to the Enforcement Directive, the court concluded – contrary to the more limited view expressed by Advocate General (AG) Jääskinen in his Opinion – that the jurisdiction conferred by the third sentence in Article 11 of the Enforcement Directive allows national courts to order an intermediary to take measures that contribute not only to terminate infringements committed through its services, but also prevent further infringements.

Principle #3 - In respect of this principle it should be noted that, while EU law leaves the conditions and modalities of injunctions to EU Member States, the CJEU has referred to the need of complying with different types of sources that include, inter alia: the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (notably copyright protection, freedom of expression/information, freedom to conduct a business, protection of personal data), the Enforcement Directive (in particular Arts 2(3) and 3 therein), the E-commerce Directive (including Art 15 therein).

Principle #4 - In UPC Telekabel [Katposts here] the CJEU held that this particular type of injunction is indeed available under EU law. Importantly, and contrary to the view expressed by AG Cruz Villalón, a blocking injunction does not have to be specific: its addressee should determine the specific measures to be taken in order to achieve the result sought.

Principle #5 - The final principle, which the CJEU has adopted in the context of a reference also concerning the availability of intermediary injunctions (The Pirate Bay case [Katposts here]), serves to note that - when we speak of intermediaries - we should not (or perhaps, no longer) think about them solely as addressees of injunctions or as subjects that might lose (if the relevant conditions are satisfied) their safe harbour protection, but also as subjects that - in certain contexts - might be directly liable for the infringement of third-party IP rights. The decision in The Pirate Bay has potentially begun a new chapter in the topic of intermediary liability (and also injunctions), the relevant implications of which are currently being worked out. While it is true that the CJEU case concerned a rather 'rogue' platform (The Pirate Bay), are the considerations made in that decision more broadly applicable? In this sense, a case pending before the German Federal Court of Justice and concerning the primary liability of YouTube [reported by The IPKat here] might assist in understanding more fully the implications of CJEU case law.

[Originally published on The IPKat on 21 May 2018]

Comments

Post a Comment