Facebook found liable for hosting links to unlicensed content

|

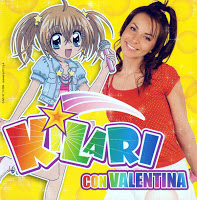

| Kilari and Valentina Ponzone |

For the first time under Italian law a platform (Facebook) has been found liable for hosting third-party links to unlicensed content.

The decision was issued by the Rome Court of First Instance a few days ago: it is Tribunale di Roma, sentenza 3512/2019.

The judgment is both interesting and important, also considering the YouTube referral (C-682/18) currently pending before the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) [Katpost here].

Let's see more in detail what happened and how the Rome court reasoned.

Background

Broadcaster Reti Televisive Italiane SpA (RTI) and singer Valentina Ponzone sued Facebook over the creation, on the latter, of a profile that hosted unlicensed videos and defamatory comments relating to Ms Ponzone's performance of the intro to the Italian version of Japanese animated TV series Kilari. The profile also contained a photograph of Ms Ponzone dressed up as character Kilari, and links to videos hosted on YouTube and consisting of extracts from the animated TV series.

Facebook received 5 requests to deactivate the profile at issue, as well as removing all images, videos, and links. The relevant profile was only removed in 2012, ie 2 years after the first request had been sent.

RTI and Ms Ponzone submitted that Facebook would be liable for defamation and violation of image rights, as well as infringement of RTI's exclusive rights over Kilari and trade mark 'Italia 1'. They also claimed damages for EUR 500,000 (EUR 250,000 for Ms Ponzone and EUR 500,000 for RTI).

Facebook responded that, first, the Italian court would have no jurisdiction and, second, that no liability could subsist, it being eligible for the safe harbour protection under Article 16 of the Italian Legislative Decree 70/2003 (corresponding to Article 14 of the E-commerce Directive) and having no monitoring obligation as per Article 17 of the Decree/Article 15 of the Directive.

The decision

The Rome court dismissed both arguments raised by Facebook.

Jurisdiction

With regard to jurisdiction, the judge found that Article 5(3) of the Brussels Convention would apply. The place where the harmful event occurred must be intended not as the place where the infringing content was uploaded, but rather as the place where the damage is felt, that is where the victim resides or exercises its economic activity. In this case, this place would be Italy. This conclusion would be in line with CJEU case law on the Brussels I Regulation recast, in particular the decision in Hejduk [here].

Thus, the relevant jurisdiction clause in Facebook's Terms of Service would be inapplicable to the case at issue, as it relates to contractual disputes between the platform and its users, not actions brought in tort.

Liability

With regard to the content of the comments, the court concluded that they had defamatory character.

Of particular interest is the conclusion reached with regard to the publication of links. By referring to relevant CJEU case law - in particular the recent decisions in Filmspeler [here] and Renckhoff [here] - the Rome court held that [the translation from Italian is mine]:

The publication of RTI's audiovisual content through Facebook is an act of communication to a new public in that it is a public other than the one authorized by the claimant. Indeed, the links published through the Facebook page led not to content published by RTI itself through its own platform, but rather content published through a third-party site (YouTube) not authorized by RTI to making available the audiovisual content at issue. It follows that, lacking a specific authorization by RTI, the making available to the public (through a third-party portal) of the intro to animated series 'Kilari' must be considered unlawful.

The above appears to suggest that to display content on YouTube the relevant rightholder's permission would be needed, but the court failed to elaborate on this (important) point.

What the court discussed a bit more at length is (1) how the infringing content is to be notified and (2) the liability of Facebook.

The Rome court first recalled that the safe harbour for hosting providers only applies to providers that are passive. If a provider acquires knowledge - ex post - of the infringing activity, it has a duty to act expeditiously to remove or disable access to the relevant (notified) content.

According to the Rome court [this is not the first time: see, eg, here] to notify a provider of an infringing activity it is not necessary to submit the relevant URL for each and every infringement. The first request that RTI submitted contained a URL to the Facebook page where it was possible to subscribe to a group that would allow one to read the relevant comments and view, by clicking on the links, the videos. In any event, [again, the translation is mine]:

the indication of the URL is technical information which does not coincide with the individual infringing contents available on the digital platform, but only represents the 'location' where such contents are available and, as such, is not an indispensable element for their localization

According to the Rome court, Facebook did not act in accordance with the level of diligence required for a hosting provider:

The operators of the Facebook portal failed to adopt all measures that could be reasonably expected in the case at issue to prevent the unlawful making available of content and, as a result, they failed to act in accordance with the diligence that might be reasonably expected from the hosting provider

As such, the court found Facebook liable - by omission - for violating the personal rights of the claimants, Ms Ponzone's image rights, and infringing RTI's exclusive rights over the audiovisual content. No trade mark infringement was found as Facebook had not 'misappropriated' the registered sign. The court also awarded damages for little over EUR 30,000.

|

| AnimeKats: Sailor Moon's Luna |

Comment

The decision is interesting for a number of reasons, but in particular in relation to the issue of knowledge of a hosting provider of third-party infringing activities.

One of the questions referred in YouTube is indeed the following [the translation from German is mine]:

Does actual knowledge of the unlawful activity or information as referred to in that provision [Article 14(1) of the E-commerce Directive] and the awareness of the facts or circumstances from which the illegal activity or information becomes evident have to be in relation to specific unlawful activities or information?

This question seeks clarification on the notion of ‘knowledge’ (and ‘awareness’) within Article 14(1) and also, as it appears, the degree of specificity of a takedown request. The CJEU has not yet had a chance to provide specific guidance on this point. However, from the decision in L’Oréal, there appears to be a duty of specificity on the side of the rightholders. In that case the CJEU suggested that notifications of allegedly illegal activities or information that “turn out to be insufficiently precise or inadequately substantiated” could not preclude the availability of the safe harbour to the provider.

In addition, one might wonder whether a duty of the hosting provider to remove or disable access to infringing content even absent knowledge of specific unlawful activities or information might be contrary to Article 15 of the E-commerce Directive. In this sense, in its twin judgment in Scarlet and Netlog, the CJEU found that SABAM’s request to the providers at issue in those cases (respectively, an access and a hosting provider) to prevent the making available of works in its repertoire would be tantamount to imposing a general monitoring obligation.

The reasoning of the Rome court does not instead appear too helpful with regard to what is probably the KEY question in YouTube, that is whether the operators of a platform of this kind could be regarded as directly liable for the content uploaded by users ... à la Pirate Bay [Katposts here].

Indeed, the Italian court appeared to focus more on the dichotomy safe harbour availability / unavailability, rather than a direct responsibility (and, therefore, liability) of Facebook operators for - inter alia - linking to infringing content. Nonetheless, the conclusion of the Rome court was that Facebook operators would be liable - inter alia - for infringing RTI's rights under Article 79 of the Italian Copyright Act.

In all this, it will be crucial to see what the CJEU decides in YouTube, although the question of liability might become less pressing. When the EU court decides the referral, at the policy and legislative level we may indeed have an answer already - in the affirmative (certain platform operators are directly responsible for the making available of user-uploaded content). The new Directive on copyright in the Digital Single Market might be indeed at the national transposition stage by that time.

[Originally published on The IPKat on 21 February 2019]

Comments

Post a Comment